How conservation scores affect CRISPR/Cas9 guide efficacy prediction

The Problem

CRISPR/Cas9 guide efficacy varies greatly, depending on the guide sequence and other factors. Choosing the best guide for your CRISPR gene knockout experiment can be tough, and several models try to help by providing in-silico guide efficacy predictions based on experimental cut efficacy data. However, gene knockout success suffers from another issue which cannot be circumvented by finding the most efficient guides:

In-Frame indel

When a double strand break, induced by the Cas9 molecule, occurs, the cell repairs the cut site using its non-homologous end joining mechanism. This takes some time, in which nucleotides can fall off, or bind to, the open ends of the DNA. For this reason, the repaired gene contains a frameshift in most of the times. This frameshift renders the translated protein functionless which conforms to a successful gene knockout. Though the number of times where an in-frameshift occurs is not negligible (about one third). Even though, a few amino acids are changed, added or deleted in the translated protein, it may still be functional as most of the amino acids are not changed.

Solutions

Basis of my experiments was the FC and RES dataset from Doench et al. It contains the experimentally determined guide efficacy of more than 5000 guides along with their protospacer sequence, in-genome position and other data.

Targeting sensible locations

One approach to counter this issue, is to target functional domains in proteins. This way, a change of a few amino acids only can have a drastic effect on the function of the protein. This has been reported to improve knockout success rate by Shi et al. though Doench et al. could not exploit this information to improve their model.

Thinking one layer down, there is another source of information which can help targetting genomic regions with higher success rate: Conservation scores. I used the phastCons100way dataset which aligns the human genome to 99 other species and calculates conservation scores on a nucleotide basis. As Siepel et al. put it, “The primary reason for cross-species sequence conservation is believed to be negative (purifying) selection”. This makes this a potentially valueable information for a guide efficacy prediction model. Altering highly conserved nucleotides (and their underlying amino acids) is likely to render the corresponding protein useless (which corresponds to the negative selection mentioned by Siepel et al.).

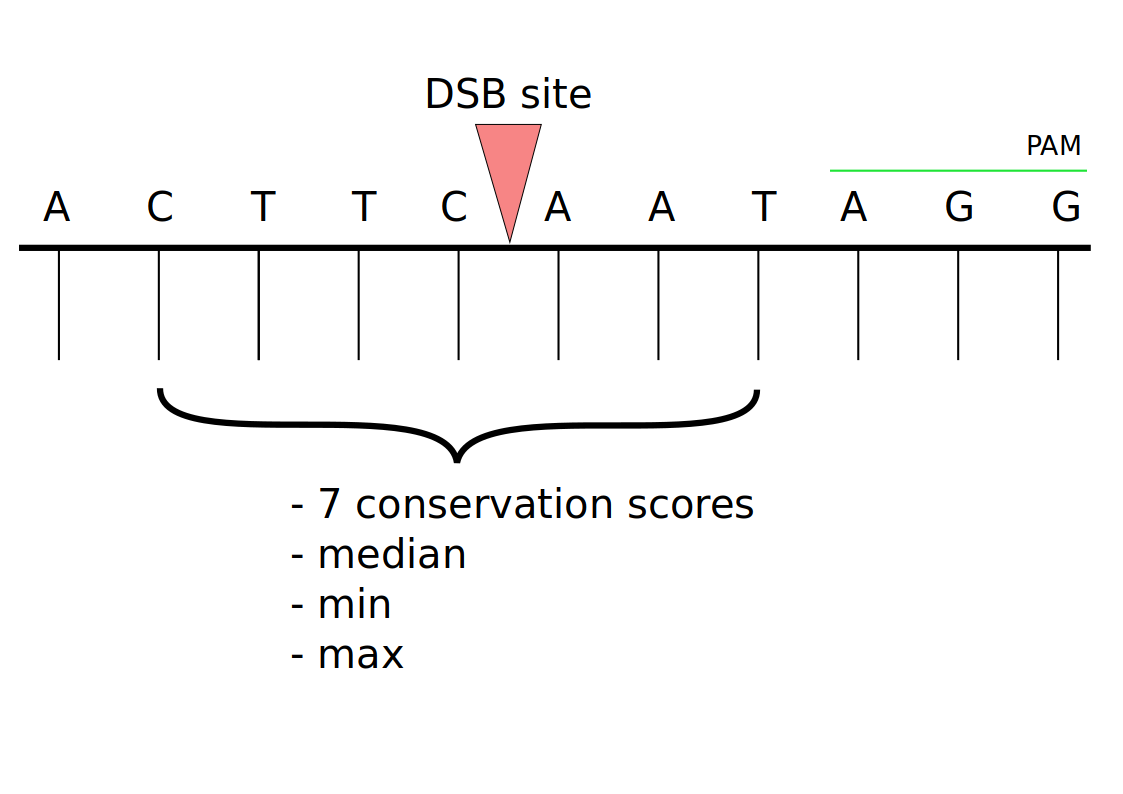

As several nucleotides can fall off at the cut site and because the underlying amino acid at the cut site is affected by various nucletiodes on the right and the left of the cut site dependent on the frame offset, I chose to extract consveration scores for the nucleotide at the cut site and its 3 neighbours on both sides. I furthermore derived three additional data. The maximum, minimum and median of the seven conservation scores.

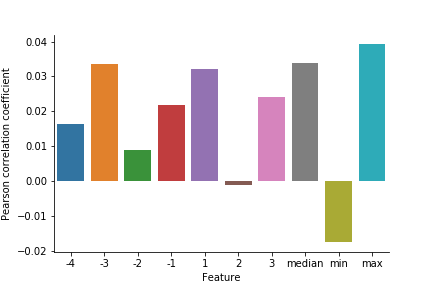

Pearson correlating these data with the experimentally determined guide efficacies showed statistically significant correlations with the highest p-value of 0.0043 for the derived maximum data.

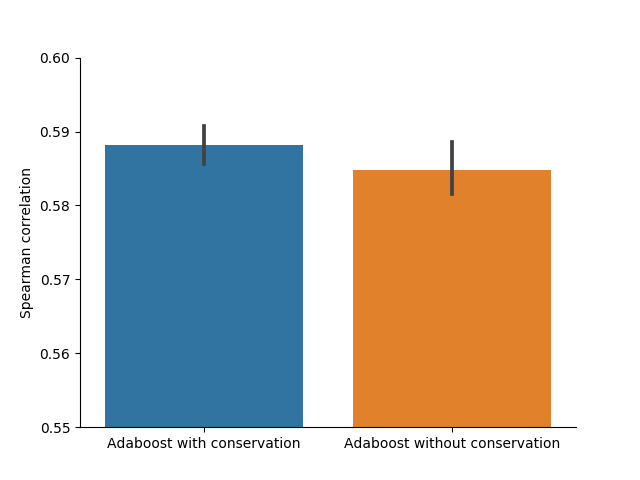

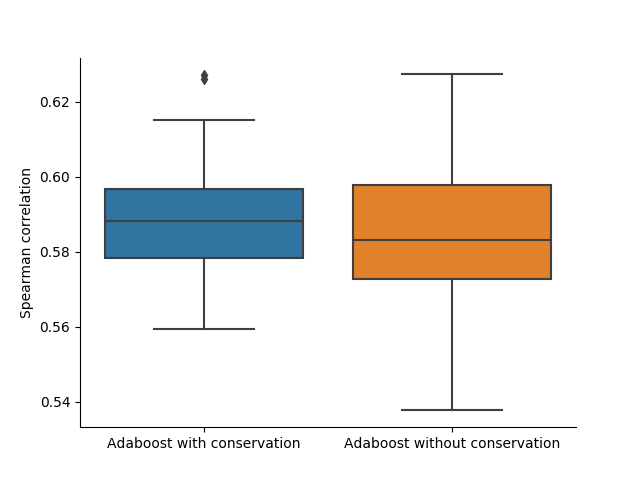

To verify the predictiveness of conservation data in guide efficacy prediction, I trained the model from Fusi and Doench et al. 200 times with random training/validation splits. 100 times I used the original feature set from their publication and 100 times I added the extracted conservation data. As seen, the mean and median performances improve with the additional information provided.

Discussion

The statistically significant correlation between the guide efficacies and the conservation scores, as well as the increase in prediction model performance when providing the model with conservation score information show, that conservation scores contain useful information to improve CRISPR guide efficacy prediction. Unfortunately the chosen model only improved slightly with a relatively high standard deviation. Future work would include to verify if other models can make better use of the conservation data or if the information value is not high enough to significantly improve model performance.

References

https://www.nature.com/articles/nbt.3437 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16024819 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25961408 http://hgdownload.cse.ucsc.edu/goldenPath/hg19/phastCons100way/ https://www.biorxiv.org/content/early/2015/06/26/021568